Life of

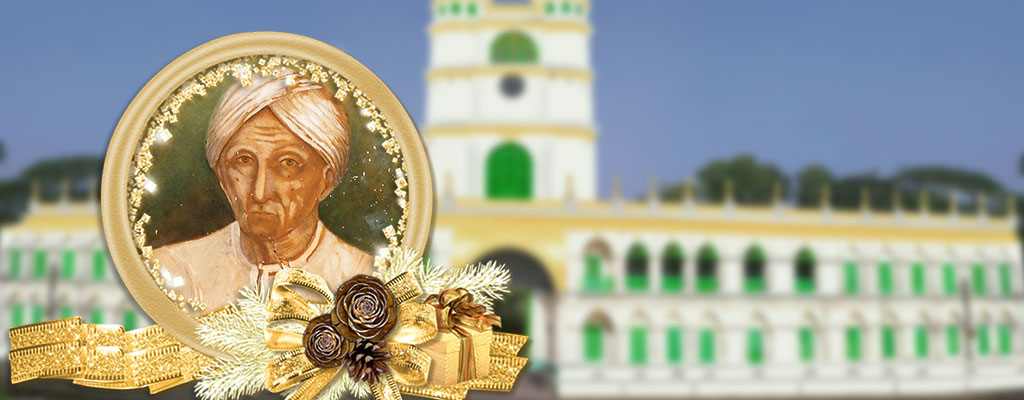

HAJI MAHAMMED MOHSIN

translate by: Mahendra Chandra Mitra

The town where Haji Mahammed Mohsin lived is our own town, Hooghly. It has a classical importance which none but a historian can appreciate. Golin or Hooghly was the town of the Portuguese General Somproyana.

Here he built a fortress at a place called Gholghat, close to the present Hooghly Jail, premises the vestiges of which are still visible in the bed of the river. The town and port of Hooghly rose into importance after the celebrated siege of the fortress in 1639 by the Emperor Shah Jehan’s troops. It is said that a thousand Portuguese were slaughtered, and 4000 men and women were taken prisoners of war. Since then, the Mogul Government brought down all the pubic records and offices to Hooghly from Satgan, which sank into insignificance by the silting up of the river Saraswati. This town was also the first settlement of the English in Lower Bengal. In1686 Hooghly was bombarded by Captain Nicholson on account of quarrel between a few English soldiers and Nabob’s troops. Hooghly was also the second city in Bengal during the palmy days of the Mahammedan rule. A line of strong buildings and a fort were then the rich possessions of the residents of Hooghly. The Mussulman inhabitants of the town still speak with admiration of its former political and military grandeur. A Fouzdar was located here with the powers of a governor and magistrate. The oldest inhabitant of the town, now living, has informed me that the whole range of buildings, wz., the Civil Court-house and the Record Office, as well as the tank in front of the Branch School, occupy the site of the palace of the Fouzdar Khan Jehan Khan. This very school-building, where we have assembled tonight, was the place where stood the Zenana-House of the Fouzdar. The buildings of Nabob Khan Jehan Khan were small in size and old-fashioned. They had nothing to testify to the taste of the Gothic architecture of the Mahammedan governor. The site of the Fort of Hooghly is that open ground north ruins of the Fort are still to be seen on the west side of the mosque known as Syed Chand. The remains of an old wall attract the attention of the archaeologist. Hooghly was chiefly inhabited by the Mahammedans even after it had come into the hands of the English for more than half a century; that was a busy day for the traders of Hooghly and Chinsurah. The Imambazar was the locale of many godowns and shops. The neighbouring town, Chinsurah, though to all intents and purposes a Dutch settlement, was crowded by many Mahammedans traders, especially the Moguls, fin the year of the Hejira 1220, the number of respectable Mogul families was counted at sixty; even upto this day some of there descendents lived there. Among the respectable inhabitants of the time, the names of Nabob Nusrut-oolah Khan of Motee Jheel, Juffer Pumba, dealer in cotton goods, Haji Kurbali Mahammed, a rich trader in Indigo, and Mea Ahsun, the rich owner of Bara-dbary, who exchanged his turban as a token of friendship with Nabob Ali Verdi Khan, are well known to us: there were others of no small fame. Casim Ali (by whose name the Hat Mallick Casim is known), Fukrut-tujjar, a powerful zemindar, rud Mir Saliman Khan are hardly forgotten. In Hooghly there were a family of Cazies marked for their piety and liberal views. The representative of this family, at that time, was Cazi Lal Muhammed.

But in the galaxy of the distinguished men of the time, the most illustrious were two individuals, whose aims of life were opposed to each other. Both figured at the same time, the one was a Nabob, the other was a Dervesh. The one sat in the lap of luxury, the other lived in an unostentatious style. The one, armed with the executive and judicial powers of a magistrate and judge, exercised an unbounded influence over his people; the other by his national sympathies and noble acts of charity to the poor won their heart. Such were the characters of Nabob Khan Jehan Khan and Haji Mahammed Mohsin; no two men were so popular in the town as these two contemporaries. But Nabob Khan Jehan Khan has left nothing behind to posterity, while the name of Haji Mahammed Mohsin is on the lips of every citizen of the town.

Haji Mahammed Mohsin sprang from an illustrious family. His grandfather Aga Fuzloolah, a rich merchant of Iran, came to India in the early part of the eighteenth century. His son Haji Fyzoolah, the father of Haji Mahammed Mohsin, one of the merchants of Moorshedabad, had extensive concerns in that city as well as in Hooghly. He however met with unexpected reverses of fortune. Haji Fyzoolah selected the town of Hooghly for his residence. Here he had the good fortune to cultivate the acquaintance of a rich and beautiful lady, the widow of Aga Motahar, whom he afterwards married. Aga Motahar was a member of the Motahar family of Ispahan. The Motahars were respectable merchants of that city, and well known for their piety and adventurous spirit. It is said that aga Motahar lived for sometime in Delhi. He was the Koleddar of Khazana, Key-keeper, of the great emperor Aurangzabe. Aga Motahar was a favorite of the emperor; he lived with his family in the apartments of the palace. An interesting story is told of the Emperor Aurangzabe’s sincere regard for Aga Motahar. One night Aga Motahar’s wife had a curious dream. An old dervish came to her and asked her if she would observe the ceremony of the Mohurrum. She was startled to hear those words from the old man, and could only answer him by shedding tears. The words of the Dervesh were, however, emphatic:- “Go you to other regions, and for the salvation of the soul observe the ceremony of the Tuzeah. The Mohurrum nights are drawing near. The moon in the sky is visible to the naked eye.” Aga Motahar found his wife weeping that night. The very idea of the subject matter of the dream was an impious one in the court of the Emperor Aurangzebe, who was a bigoted sunni. The information, however, was communicated to the Empress, and at last it reached the ears of Aurangzebe. Though the Emperor was displeased with Aga Motahar’s wife, he allowed her to go out of his capital and observe the ceremony of tuzeah in a distant part of the empire. He selected for the residence of the Motahar family the town of Hooghly, and granted them extensive and rich jageers in Jessore, Chitpoor and other places. The Motahar family then migrated from the capital of the Mogul Emperors to Hooghly, and erected the Imambara in the very place where Moorsheed Kuli Khan had founded one. The arrival of the Motahar family in Hooghly is thus accounted for. There is, however, another version of the story. It is said that, during the reign of the Emperor Aurangzebe, Aga Motahar accepted service under the Raja of Benares. The good Raja was so much pleased with him that he entrusted him with all his zemindary business. After the death of the Raja, Aga Motahar managed his estates during the minority of his son, procured for him the estates of Jessore and Chitpur. After such a length of time, without the help of written evidence, it is difficult to accept the one statement or reject the other. (Aga Motahar purchased the land on which the Imam-bara buildings stand from a rich and respectable merchant, Jaffer Pumba: it had been the compound of his cotton factory. There was also a line of building, belonging to Bibi Anaro, on the very spot where the gates of the present Imambara stand. That was said to be the Imambara of that pious lady. Aga Motahar purchased from her the land and its appurtenances. In the year of Hejira 1104, the Imambara “ Nazar Gahe Hossein, “ the holy place where presents are offered to Imam Hossein, was built. Aga Motahar in his later days did not enjoy peace of mind. Vexed with domestic quarrels, he wished several times to leave the town and go elsewhere. There was, however, an attraction in the person of his affectionate daughter, Manoo Jan Khanum, which made him stay at Hooghly: she was his pet child. A curious story is told of the way in which he she obtained the properties of her father. Aga Motahar is said to have made her a present of tabiz (armlet), with strict in-junctions not to break it till after his death. His words were obeyed, and the Motahar family were surprised to see that it contained a grant, by Aga Motahar, of all his properties in favour of Manoo Jan Khanum : the deed of gift had been sealed and signed by the donor. The mother of Manoo Jan Khanum was displeased with the conduct of her husband; and it is urged on the ground of probability, that this strange act of Aga Motahar might have led her to marry Haji Fyzoolah, then a resident of the town of Hooghly: the fruit of this marriage was Haji Mahammed Mohsin. He was born in the year 1732, and was younger to his sister Manoo Jan Khanum by eight years. Both he and his step-sister lived with their father and mother in the house of Aga Motahar: both of them were brought up there till the death of Haji Fyzoolah. A report was current that the enemies of Manoo Jan Khanum had made an attempt to poison her: this having reached the ears of Mahammed Mohsin, he communicated the information to his sister and fled from Hooghly. Since then he led the life of a Dervesh.

Though the death of Haji Fyzoolah and the sudden flight of Mahammed Mohsin had cast a gloom over the affairs of Manoo Jan Khanum, the arrival of Mirza Sala Udeen Mahammed Khan, a nephew of Aga Motahar, cheered up their prospects. Aga Motahar, on his death-bed, had left his last injunctions to marry his daughter to his nephew. At the request of his aunt, Mirza Sala-udeen came from Persia and married Manoo Jan Khanum. Both the husband and wife won golden opinions from the inhabitants of the town: their popularity was due to their large charities. In the year of Hejira 1168 Mirza Sala-udeen extended the Imambara buildings. The “Tazeah Khana” or the place for mourning, was the additional portion built by him. In the same year he established the Hat, which still goes by his name as Mirza Salah.

There is another account of the birth of Haji Mahammed Mohsin. It is said that he was born in Moorshedabad, and that his father, Haji Fyzoolah died in that city. After his father’s death his mother came to Hooghly and married Aga Motahar: the issue of this marriage was Manoo Jan Khanum. This is rather a conflicting version of the story already told; it is difficult to pronounce which statement is the more credible one. There are, however, two evidentiary facts which suggest that Aga Motahar’s widow married Haji Fyzoolah. It is said that this gentleman lived for some years in Hooghly and died here; and that Manoo Jan Khanum was older than her step brother Haji Mahammed. These facts have received corroboration from their wide-spread currency among the inhabitants of this town. A living witness of the days of Haji Mahammed Mohsin gives another account of his birth. In his view Mahammed Mohsin and Manoo Jan Khanum were not born of the same mothers. This last statement is open to criticism. If this account were true, the estates of Manoo Jan Khanum would not have devolved on Haji Mahammed Mohsin by the law of inheritance of the Imammen School. Born in the year 1732, during the reign of the Emperor Mahammed Shah, Mahammed Mohsin had witnessed, the successive changes of Government during those revolutionary periods. That was a very eventful age in the annals of India. The power of the Mahammedan rulers was on its decline. The Mogul empire had received a shock from internal discord as well as from foreign pressure. During those days the Mahrattas were disturbing the quiet villages and the busy towns of the empire. The Imperial Government was without a head. The provincial governors, who had declared themselves independent, followed the footsteps of their effeminate master. Ali Verdi Khan, the Nabob of Moorshedabad, after governing the country with an iron hand, died to bequeath his well-fought prize to a worthless grandson Suraja-Dowla, who was notorious for his cruelty, weak judgement and last, though not least, his officious quarrel with the English in Calcutta: it was then that this miserable prince enacted the ever-memorable Black Hole tragedy. The victory obtained in the battle-field of Plassey, and the supreme authority excercised by Lordlive over the political destinies of the country, were the triumphant feats of the conquerors achieved under the very eyes of Mahammed Mohsin: he was then a young man of five-and-twenty. Though possessed of intellectual powers of no small degree, he had no opportunity to cultivate them till he came to the metropolis: the country was then undergoing a change, for that was a transition period in the political life of the Mahammedans of this country. The education of youth did not, however, then attract men’s minds; the fashionable views of a few cavaliers of the court of Moorshedabad had much to do in the education of the young men of the age. Their aspirations for high donors in the service of Government ended in the hope of pandering to the impious taste and immoral inclinations of those who were in authority, and the promotion of an officer of the state had to depend upon the whimsical and capricious statements of a wrong-headed statement. As there was a change in the political destinies of the country, there was a corresponding change in social life. There was a reaction in the Council-chamber of the Vizier as in the camp of the Subadar; the shock was communicated to all the strata of society. The influence of a few foreigners, however turned the current of the thoughts of the nation to proper channels. It was in a period when new ideas were expanding and were being crystallized into the fashion of the Europeans, that Mahammed Mohsin came to live in Moorshedabad, the metropolis of Mahammedan chivalry and Mahammedan learning.

It is not easy after such a length of time to fix precisely the year of the first arrival of Mahammed Mohsin at Moorshedabad. Before he came to this city, Mahammed Mohsin had received his rudimentary education in Hooghly under the care of his father, who was a man of piety and learning. Both Mahammed Mohsin and his step-sister were taught in the elements of Persian language: their tutor was seraji, a gentleman of great pretensions. It is said that he had travelled in many countries, and had at last settled in Hooghly. His glowing descriptions of many countries and celebrated cities exercise considerable influence over his young mind. Mahammed Mohsin waited for a golden opportunity to quench his thirst for travel, till he was driven by a combination of circumstances from his father’s home, where he had spent his boyhood. On his arrival at Moorshedabad, he had the good fortune to associate himself with some of the distinguished Persian scholars of the city. He directed his attention to the study of oriental languages, in which he afterwards perfected himself when he travelled in Arabia and Persia. He was reputed to be a good Arabic scholar. Hi calligraphy was marvelously fine, a specimen of which is still to be found in the Hooghly College Library. A copy of the Koran written by his own hand still looks fresh, and is an object of admiration to the Arabic scholars of the day. I have learnt on good authority that Haji Mahammed Mohsin, in his later years, supplied the beggars with pieces of paper containing texts from the Holy Koran. So high a value was attached to his calligraphy, that it fetched a high price to the recipients.

As Mahammed Mohsin cultivated his mind, he did not lose sight of giving free scope to bodily exercises. He had a sound constitution: he was a good swordsman. He did not allow a single day to pass away without observing the routine prescribed for his bodily exercises. I heard from Syed Keramat ali, the late lamented Mutwalee of the Imambara, that Mahammed Mohsin was fond of walking. In his estimation that was an exercise in no way inferior to riding.

It is interesting to take a rapid view of the state of morals in the country when Mahammed Mohsin was storing in his mind with the literature of the Persian and Arabic writers. After the downfall of the Nabob’s government, the Omraos and the people became notorious for their corrupt conduct and immoral habits: their deceptions equaled their pretensions; their cowardice surpassed their rashness. The scenes of real life in the streets, the private residences of citizens, the camp of soldiers and the palace of the Nabob, were sad. Yet in the midst of these contradictory changes, and underneath his dark and foul fermentatiob, Mahammed Mohsin and his party were men of good sense and morality, thorough honesty and of moderate opinions.

When the signs of the times were so gloomy, the character of Mahammed Mohsin was an object of admiration and respect. That the standard of his morality was of a high order requires no proof. But, like most of the followers of Islam, in him there was no border land between morality and religion. The loftier ideas of morality are all shadowed forth in the injunctions of the Koran. Mahammed Mohsin proved himself a strict follower of the Imaimea faith: his life was a religious one: he was a Dervesh to all intents and purposes. From his boyhood, Mahammed Mohsin pursued a course of life which, in the age in which he lived, was an exceptional one. He did not marry. Even to his last days his scorn of a married life was proverbial.

Little is known of Mahammed Mohsin whilst he lived in Moorshedabad at this early age life, we are therefore obliged to leap at once over twenty-five years. Various statements are made regarding the manner in which he lived in Moorshedabad: but one thing is certain, that he led the life of a recluse. He spent his days in reading works of Persian literature and Arabian science, in writing passages daily from the Koran, and devoting himself to works of piety.

It is said that during this period of his life he travelled from one town to another in Hindustan, and had great opportunities of coming in contact with men of different races, creeds, and colour. He studied both the dark and bright features of human nature. His fund of information was never exhausted. I have learned from a respectable Mahammedan gentleman of this town, whose grandfather had the honour of being acquainted with Mahammed Mohsin, that he was the repository of all the stories of the world.

About the year of Hejira 1210, Mahammed Mohsin undertook his journey to Persia, Arabia, Turkey and Egypt; for a period of six years he travelled from one country to another. In his travels he visited the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. As far as I am aware, there is no written work of his travels. It appears that he came back to Moorshedabad in the year of Hejira 1216.

While Mahammed Mohsin was travelling all over the distant countries, the affairs of Manoo Jan Khanum in Hooghly were not prosperous: she had the ill-luck of wearing the weeds of widowhood, her good husband died in the prime of life, and she was anxiously waiting for the arrival of her step-brother. Her strong desire was to place all her rich properties in the possession of Mahammed Mohsin. At last, at the solicitation of his sister, Mahammed Mohsin came to Hooghly in the company of two distinguished Mahammedan gentleman, Rujub Ali Khan and Shaker Ali Khan, both of them men of ability and sterling merit. Both these men were a religious turn of mind, and were shortly companions of Mahammed Mohsin: both of them were acknowledged to be men of business. Mahammed Mohsin came back to Hooghly already an old man, he was above fifty, but still in full vigor of mind and body. His arrival in Hooghly was welcomed by the inhabitants of the town. So great was his popularity that public rejoicings were made in his honour. Manoo Jan Khanum, with the other members of her household, was highly pleased with Mahammed Mohsin; but she did not live long. After the death of her husband she had herself taken the whole responsibility of managing her affairs. Well versed in zemindary business, she was liked bu her agents and tenants. In her later days she was seen to hold her sittings in a Cutcherry with a veil on her face. She was described as a woman of strong intellect, large information, and some knowledge in the Persian language. A well-known anecdote speaks of her strong common sense. Nabob Khan Jehan Khan sent word to her with proposals of marriage. The reply of Manoo Jan Khanum was remarkably bold; she refused to marry Nabob Khan Jehan Khan. “No” she said. I will not consent to be the wife of a man whose desire is to marry me, not for the sake of affection, but for money.” She breathed her last in the year 1210 B.S., regretted by all who knew or heard her name. Her rich properties and princely fortunes were inherited by Mahammed Mohsin. The well-known zemindaries of Pergunnah Syedpore and Pergunnah Sobhnal were thus inherited by him. After the death of Manoo Jan Khanum, there was an attempt on the part of one Bunda Ali to take possession of her properties. He represented himself to be the son of Mahammed Mea, who was said to be the adopted son of Manoo Jan Khanum. Bunda Ali had brought a suit against Haji Mahammed Mohsin. The result of the litigation was favourable to the later gentleman; and Bunda Ali died heart-broken in his house (which is now known as the Municipal House) close to the Imambara.

Our history of Mahammed Mohsin has now come to a period which was the best one in his life. We now view him in another aspect, namely as a philanthropist. He now exhibits himself to us not only as a wise man, but as a great man. His private and public acts of charity demonstrate the truth of the assertion, that an unselfish man is always the best man in the world. To him the world is his home: his sympathies are not swayed by personal motives or inclinations: to him the whole human race is a brotherhood. Mahammed Mohsin is a worthyrepresentative of this class of people.His acts of private charity were no less conspicuous than his well-known charitable acts for the public at large. These acts are the proofs of the nobleness of a mind that sympathises with distressed poverty. It is said that the practice of Mahammed Mohsin was to take nightly walks in the streets of the town, with the avowed object of feeding those who could not procure their food after the whole day’s labour. An anecdote is told of him. One evening he passed by the hut of a poor woman who had a number of child to feed. It was late in the evening that he heard the cry of the children for bread. The starved mother shed tears in vain, she had no one to help her. The heart of Mahammed Mohsin was touched. He immediately came forward with a supply of loaves for the children of the poor woman, and since then looked after them with a parental care. Moulvie Asraf-u-deen Ahmed, the present Mutwalee of the Hooghly Imambara, has kindly mentioned to me another well known story of Mahammed Mohsin’s charity to the poor. It is said that one night he came across a blind man and his family in a small hut in the town; the blind man’s wife beat her husband for not procuring food for the family. Mahammed Mohsin happening to know this, secretly came to the windown and threw silver coins on the floor. The joy was boundless, and the whole family thanked aloud Mahammed Mohsin, though nobody knew who was the giver. Such are the stories which are afloat of Mahammed Mohsin’s private charities: his helping hand was extended to all. A Mahammedan gentleman of this town has furnished me with a list of pensioners who lived on his bounty; many of them received annually a sum of Rs. 500. Their sons and grandsons and grand-daughters still receive handsome pensions from the estate of Mahammed Mohsin. I hope I do not tire your patience with recording these noble acts of a truly great man who, though no longer in the land of the living, is still remembered with admiration and gratitude. Gentleman, picture to your mind an old man of seventy, surrounded by a circle of needy beggars who are struggling in life for bread. He stretches his hands full of silver and gold and pours them into their empty ones. He feels for them for his heart is touched by that universal sympathy for others which alone ties the human brotherhood together.

To speak of his acts of public charity, I have only to ask to look at what is written over the walls of Imambara in capital letters. “ I Haji Mahammed Mohsin, son of Haji Fyzoolah, son of Aga Fuzloolah, inhabitant of Bundar Hooghly, in the full possession of all my senses and faculties, with my own free will and accord, do make the following correct and legal direction: That the zemindary of Pergunnah Quismat Swedpore appendant to Zillah Jesore, and Pergunnah Sobhnal also appendant to Zillah aforesaid, and one house situated in Hooghly (Known and distinguished as Imambara), and Imambazar and Hat (market) also situated in Hooghly, and all the goods and chattels appertaining to the Imambara agreeably to a separate list; the whole of which have devolved on me by inheritance, and of which the proprietary possession I enjoy up to the present time; as I have no children nor grandchildren nor other relatives who would become my legal heirs; and as I have full wish and desire to keep up and continue the usages and charitable expenditures (Murasam. O-Ukhrajat-i-husneh) at the Fateha and of the Huzrut ( on whom be the blessings and rewards) which have been the established picture of this family, I therefore hereby give purely for the sake of God, the whole of the above property, with all its rights, immunities and privileges, whole and entire, little or much in it, with it, or from it, and whatever (by way of appendage) might arise from it, relate or belong to it as a permanent appropriation for the following expenditures:- and have hereby appointed Rujub Ali Khan, son of Sheikh Maharnraed Sadeq, and Fakir ali Khan, son of Ahmad Khan, who have been tried and approved by me, as possessing undersanding, knowledge, religion and probity. Mutwalees (trustees or superintendents) of the said Waqf or appropriation, which I have given in trust to the above two individuals-that aiding and assisting each other, they might consult, advise and agree together in the Joint management of the business of the said proportion, in the manner as follows:- that the aforenamed Mutwalees, after paying the revenues of Government, shall divide the remaining produce of the Mehals aforenamed into nine shares, of which three shares, they shalldisburse in the observance of the Fateha of Huzrut Syud-i-Kayunat ( head of the creation) the last of the prophets, and of the sinless Imams ( on all of whom be the blessings and peace of God), and in the expenditures appertaining to the Ushra of Mohurrum Oolhuram (ten days of the sacred Mohurrum), and all other blessed days of feasts and festivals; and in the repairs of the Imambara and Cemetry: two shares the Mutwalees, in equal proportion, shall appropriate to themselves for their own expenses, and four shares shall be disbursed in payment for the establishment, and of those whose names are inserted in the separate list signed and sealed by me. In regard to daily expenses, monthly stipends of the stipendaries, respectable man, peadas and other persons, who at this present moment stand appointed, the Mutwalees aforenamed after me, have full water to retain, abolish or discharge them as it may appear to them most fit and expedient, I have publicly committed the appropriation to the charge of the two above named individuals. In the event of Mutwalee finding himself unable to conduct the business for appropriation, he may appoint anyone who may think most fit and proper, as a Mutwalee to act in his behalf. For the above reasons this document is given in waiting this 19th day of Bysakh, in the year Hejira 1221, corresponding with the Bengal year 1213, that whenever it be required it may prove a legal deed.” This is the celebrated Endowment deed of Mahammed Mohsin. It has received a legal construction in the hands of the British Government, as it was written in a catholic spirit. The spirit of the Hooghly Imambara shows that Government, under the provisions of Regulation XIX of 1810, was obliged, in consequence of sundry corruptions of the former Mutwalees, to take the office of the Towlout upon themselves, and the business of the management was made over to the Board of Revenue and the Collector of Revenue. The expense of the Imambara and the appointment and dismissal of servants belonging to it rested with the collector and Magistrate of the District and the surgeon of Hooghly. In due course of time the active management of the business of the endowment fell into the hands of the local Agent’s office under the provisions of Act XX of 1863. The local agents are Joint-Magistrate and the Collector of Revenue.

It appears from the records of the year 1843 (seven years after the intereference by government with the management of Mahammed Mohsin’s estates) that Government by a judicious arrangement appropriated the income of the Waqf estates for the establishment of an English College, a Moosafur Khana and a Hospital. The total expenditure of the College (both for the English and Arabic classes) in 1843 amounted to Rs. 65,964. This large sum was taken from the shares of the Mutwalees and also from the shares allotted to the Tazeadaree. There was a party of Mahammedan’s that advocated that the terms of the Deed of the Appropriation only authorize expenses of the Tazeadaree, for the exclusive maintenance of which it was said that the Wakq had been made. They argued that they did not allow for the expenses in the College. But such an argument is not a tenable one. I have said that a liberal construction has been put on the deed, and the intention of the donor has received proper interpretation. Those petty quarrels regarding the terms of the deed, which were so rife among a class of discontented Mahammedan’s of the town, are now things of the past. The fund of the Appropriation is applied not only for the religious observances of the Tazeadaree, but also for the education of the boys of the town and its suburbs. A hospital attached to it is a great boon to the inhabitants of the town. But while our Government, by a wise arrangement, appropriated the Endowment fund to the maintenance of the College, special privileges were accorded to the Mahammedan’s. By a recent resolution Government has exclusively appropriated a part of the Fund, which was hitherto applied for the maintenance of the Hooghly College to the education of Mahammedan students. The tuition fee of a Mahammedan student in Hooghly College is only a rupee per month. In other colleges it is 1/3rd of the regular schooling fee, the remainder been supplied from the Maheshana Fund. The Madrassah’s of Hooghly, Dacca, Chittagong and other places are also provided from this fund. Handsome scholarships are awarded to the Mahammedan lads.

The annual income of the Syedpore trust estate which is remitted to Hooghly is Rs. 60,000. This sum is divided into four parts. One – ninth share goes as they pay of the Mutwalee; another one-ninth share is appropriated to the expenses of the Madrassah’s. Three-ninth shares is expended for religious purposes, under the management of the Imambara Committee which consists of five members. The remaining four-ninths share is at the disposal of the Local Agents. From this last share the charges of the Hospital and Charitable dispensary are provided. The expenditure of the Hospital in the year 1878-79 came up to Rs. 6,977. The balance of the four-ninth share at the end of 1878-79 was 1,40,000. The expense of maintaining Hostels were Mahammedan boys are provided with board, clothing and medicine is not to be passed over unnoticed; these Hostels are attached to be five Madrassah. The number of students who were admitted into this charitable institution of Haji Mahammed Mohsin is not a small one. In the Hostel at Chinsurah there were more than 100 students. Government has also purchased out of the Mohesena Fund a well ventilated and large building for their accommodation at the cost of Rs.25,000.

The expense for the observant of the religious cere-is also a very heavy item. During the Mohurrum days thousands of poor people are daily fed. For all parts of the country and all the neighbouring villages, thousands of men and women flock to the town of Hooghly for the purpose of making presence to Imam Hossein; and, with the beating of the tom tom, the cry of Hassan and Hossein, fills the air amidst the tears of pious Mahammedan gentleman. I do not wish to trespass on your time in enumerating to you these acts of the charities of Mahammed Mohsin as they are familiar to you. The total annual expenditure of the Mohurrum ceremony comes up to 5 to 8,000 Rs.; that of Romzan9 to 10,000 Rs.; that of other ceremonies which are celebrated in every month or at an interval of two or three months, may be estimated at 7 to 8000 Rs. Such are the public charities of Mahammed Mohsin. He has given large and valuable properties to the public for high and noble purposes. The inhabitants of Hooghly are indebted considerably to him. Manu Hindu and Mahammedan citizens of the town owe their education and status in life to him. It will be no exaggeration, to say, that in this very Hall many of my friends who are listening so attentively to the biography of this illustrious philanthropist, cannot repay the innumerable benefits which they have received from the munificient charities of a man who “though dead yet speakeath.”

“The good abides. Man dies. Die too,

The toil, the fever and the fret;

But the great thought – tho upward view

The good work done – these fail not yet!

From sire to son, from age to age

Goes down the growing heritage.”

Mahammed Mohsin was a patron of Learning. In his life-time he tried to establish a school for the education of Hindu and Mahammedan boys. The learned Moonshees, Ahmed Khan and Bukaula Khan, were in his service. A few days after his death, a regular school was established in the Imambara under the patronage of the Mutwalees. Many of you have heard the name of Francis Tydd; he was a well-known teacher of the Imambara School. It was owing to his indefatigable exertions that the school proved to be a successfully institution. It was amalagamated with the Hooghly College in the year 1836. I have learnt that Mahammed Mohsin was fond of music. In the cool evenings as well as in moonlit nights he would sit with his friends and listen to the songs of Bhola Nath sing. This a gentleman was a resident of Jessore and a great favorite of Haji Mahammed Mohsin.

The life of a good man cannot be more profitably seen than in his treatment to his servants. I have heard from a living witness of Mahammed Mohsin’s charities, that he was a kind master. A story is told of his love of his servants. One of his boy-servants (Gazi by name) learnt that his sister was on her dying bed, and having been summoned to attend her, he went up accordingly to his master, who not only granted him leave of absence for a few days, but also handed to him a bundle, which was said to contain medicine for his sister. The boy, whilst opening it at his sister’s house, was surprised to find some silver coins as a part of its contents.

We now view Mahammed Mohsin in another light, that of a moral teacher. True, his life was the life of a pious Mahammedan-the follower of Islam; but do not his character and the incidents of his life speak alike of the breadth of view, the liberality of sentimentand the universal sympathy for others, which a teacher of the catholic religion instills into our mind? In his dealings he made no distinction between Hindus and Mussalmans, and, to his credit be said, that he patronized many Hindu gentleman; some of his amlahs and servants were Hindus. In delineating the character and incidents of the life of the Mahammedan gentleman like Mahammed Mohsin, it is curious to record his aversion for meat. His havit was to shave his beard and moustachious.

Mahammed Mohsin, for a continued period of nine years lived in Hooghly. One of the Nabobs of Dacca wrote him a letter requesting him to visit that city. It appears that he did not comply with the request of his friend. In the year of the Hejirah 1226, he however undertook a journey to Jessore, where he lived for a short time.

Amidst all his good works, Mahammed Mohsin lived to a good old age. He spent his last days in the observance of religious rites. He served his country in all the modes in which benevolence can express himself. He was eyes to the blind and feet to the lame. He served the cause of religion and benevolence.

At length in the year of the Hejira 1227, symptoms appeared of feebleness and disease, and on the 24th day of Zikilda 1227, Mahammed Mohsin breathed his last. That was a gloomy day to the little world of the Hooghly people; the news of his death spread far and wide to the country, and everyone felt the that one of the best friends of humanity had passed away. On the 29th November 1812 a procession composed of simple citizens, labourers, rich and poor men followed silently his corpse, borne by friends among whom were Rujub Ali Khan and Shaker Ali Khan. Respect, affection, gratitude and sorrow were written on every countenance and audible in every word uttered by the people gathered on the occasion. The last ceremonies were observed with studied silence amidst the tears of those who stood beside the grave. His remains were led down in the very ground where his step-father, Aga Motahar, his sister Manoo Jan Khanum and his brother-in-law Mirza Sala-udeen-Khan, had taken their rest and where he, too,

Sleeps__

The good man’s rest is his,

And in our memory’s strong regard

His life shall ever nobly shine.

His admirers perhaps did not choose either to give him a splendid or magnificient tomb, or write even an epitaph on his grave; but will not his good works from sire to son commemorate his memory as a public benefactor of Hooghly? Anually a fateha is made on the 24th Zikilda: the annual expenses are provided from the esatate Bag Belour on the appointed day the following prayer for the benefit of his soul is read:- “O God, increase time love upon him with all his family and let him enjoy peace on the day of judgment for the sake of the Prophet Mahammed (may peace be upon him), he who was the first and last of prophets; and O God, do not separate him from Mahammed and may the curse of the almighty fall upon him who was the Zalim, tyrant and usurper of the lawful rights of the descendants of Mahammed. O God, give him peace in heaven forever and ever, even after the day of judgment.”

Such was the life of Mahammed Mohsin. His life is the lesson which many a rich man may study with advantage: it will teach him how to seek good ends by worthy means: and how that the youthfulness of a man’s career is measured alone by good works done by him. By the terms of the Endowment deed, the rich Wakf estates of the donor came into the management of the Mutwalees appointed by Mahammed Mohsin. A brief history of their successors in office will not, I hope, he without some interest.

During the life-time of Mahammed Mohsin and after his death, Rujub Ali Khan, and Shaker Ali Khan managed the wakf estates. In 1220 B.S. Shaker Ali Khan died, and the management of the estates came into the hands of the surviving mutwalee Rujub Ali Khan, and Baker Ali Khan, the son of Shaker Ali Khan. On the 1st Mag of 1220 B.S. (Hejira 1228) Rujub Ali Khan appointed by a deed of trust his son “Wasiq Ali Khan alias Mugul Jan a trustee in his place. The trust-deed of Rujub Ali shows a legal acumen which is complementary to him; it was the subject of discussion and criticism in the Sudder Dewanny Adawlut in the year 1836. Both Baqer Ali Khan and Wasiq Ali Khan had the right to manage the estate. Inspite of this, the Board of Revenue and the Collector of Hooghly, acting under the provisions of Regulation 19 of 1810, on the 16th of November, 1815 deputed one Syed Ali Akbar Khan as Ameen and temporary manager, with instructions to pay wages of the establishment and the allowance of the Mutwalees, and afterwards made over to his charge the lands attached to the Endowments.

The consequence was that the estates fell into arrears to Government, and the business of the establishment was greatly impeded. It appears from the order of the Collector of Jessore, dated the 9th July, 1816 that the trust was restored to the Mutwalees. The Board also sanctioned the proceedings of the Collector. Wasiq Ali Khan and Baker Ali Khan discharged the Government revenue by means of loans raised for that purpose. In September, 1818 the Board of revenue, however, again removed the trustees from the management of the Waqf estates, and entrusted it again to Syed Ali Akbar Khan. Meanwhile Baker Ali Khan became insane. Wasiq Ali made strenuous efforts to get back the management of the properties, but the Board of Revenue positively refused to agree to his proposals. He then launched himself into litigation. He filed a regular suit against Government, maintaining that the Revenue authorities acted illegally in depriving him of the trust. This suit was decided by the well-known Zillah Judge, Mr. D.C. Smythe, against the trustee, and his judgement was finally confirmedby the Lords of the Privy Council. During the period of litigation, which continued for several years, only a small part of the annual income was expended, and upwards of seven lakhs of rupees were thus added to the property by which the annual income was nearly doubled. The balance in Company’s paper amounted to Rs. 7,47,010. The Board of Revenue, in 1831 offered the following suggestion to Government;- “The most obvious purpose to which the surplus could be applied, with reference alike to the perpetuation of the founder’s name and to the promotion of useful knowledge, not entirely of a secular character, would be the establishment of a Madrassa. In which, in the first instance, Mahammedan learning might alone be taught , but which at no distant period, it might be hoped, would willingly receive the solid advantages of European science.” The report was left for the consideration of the General Committee of Public Instruction. A question was put by the Committee to Government whether the interest of the accumulated funds 7,47,010. Rupees is to be applied to the maintenance of the College, or to be blended with the income of the Imambara. The General Committee further added in their report, that there was no special provision in the Endowment deed for a Madrassa, but they, in conclusion, submitted that as long as the main object of the testator was looked to, the appropriation of the surplus funds to any other purposes of a benevolent character for the benefit of the Mahammedan population was desirable. The correspondence on the subject continued for a period of 3 years, during which period the surplus funds accumulated to Rs. 8,61,100. After a full consideration, the Governor-General in Council gave orders for the establishment of a College for general instruction.

Sir Charles Metcalfe, then acting as Governor-General of India , in a letter dated October, 1835 sketched out a scheme for the appropriation of the income of the Jessore estates of Haji Mahammed Mohsin, a plan which is still carried out in its integrity. An illusion to it has already been made in these pages. In the latter part of his resolution the following passge-occurs;- “In this manner His Honor in Council conceives that the pious and beneficient purposes of the founder of the Hooghly Endowment will be best fulfilled; and under the wide latitude given for the determination of the specific uses to which any surplus funds of the estates are to be appropriated, he cannot see that the assignment of the surplus which has arisen in this instance, partly from the delay in consequence of the litigation, and partly from the fines realized from the mode of management, applied to purposes of education in the manner stated, will be any deviation from the provisions of the deed.” The immediate consequence of the said resolution was the establishment of the Hooghly College on the 1st of August, 1836. It would be tiresome to you to go further into details of the Endowment.

By the orders of Government he was suspended, and in his place Moulvie Zomirudeen Khan alias Meroo Mea, was appointed. His service lasted for ten months only; but he is remembered very well in the town. He introduced the distribution of daily food to the poor. The next Mutwalee was the late lamented Syed Keramat Ali, a Mahammedan gentleman of ability and learning. He enjoyed the reputation of being a good Persian and Arabic scholar, and had some knowledge of the higher branches of mathematics. He made an attempt to trisect an angle Persian. The demonstration has been translated into English by Syed Ameer Ali. Syed Keramat Ali was a sudder Ameen in Joanpore, and did good service to Government. He was selected by Government to manage the Mahammed Mohsin estates. A worthier man could not have been found. Though in his latter days he appeared to be unpopular among a class of Hindus, he did good work for the town of Hooghly. The splendour and magnificence of the Hooghly Imambara are due to his taste. By tho Maheramat Ali wasgreatly respected. He died in the year 1875, 10th of August, and has been succeeded by our present learned Mutwalee Moulvie Asref-Udeen Ahmed, son of the late Nabob Ameer Ali Khan Bahadoor, a gentleman who has already gained considerable popularity by his affiable manners and his kind disposition.

Life History Of HAJI MAHAMMED MOHSIN

The Great Saint of 17th Century of Bengal Haji Mohammed Mohsin

2. Haji Mohamed Mohsin’s paternal grandfather Agha Faizullah, a merchant prince of Persia moved by the spirit of adventure then well known to Persians came to seek his fortune in India in the beginning of the 18th century, and settled for a long time at Murshidabad, where he carried on an extensive trade.

3. The flourishing port of Hooghly next attracted his attention and finding the place a convenient trading centre he sheltered himself here. His sons Haji Faizullah, whom he had left a short time, also joined his father. It was in Hooghly that the name of his famous grandson Haji Mohammed Mohsin, is shining in all splendour and solitary grandeur.

4. At that time there was in Hooghly, a wealthy Persian merchant of great renown named Agha mothar who having won his way at the court of Aurangzeb during the closing years of the emperor’s reign, came to Hooghly, and started a big trade in salt. It is with the fortunes of this great man that we are chiefly concerned here. So well did he manage his business with the help of his men, of whom Haji Faizullah, his sisters son, was one that in a short time he became one of the wealthiest men in the province. With increasing properties he extended the sphere of his activities and appointed Haji Faizullah his agent of Surat. With his vast riches, Agha Motahar purchased several properties in various mahals. Having reached the zenith of worldly prosperity, like a pious Muslim of the Imamia sect, he turned his attention to the attainment of spiritual blessedness, which is end of our life on earth. In addition to his pious and charitable acts he obtained permissions to renovate the fine Imambarah of Murshid kuli Khan, the viceroy of Bengal and thus realized the cherished object of his life. He kept a big establishment of attendants and servants. For the observance of his religious ceremony, especially the moharrum mourning days, he had set apart a portion of his property called sobhna. He had 3 wives, of whom the third was Zainab Khanam, from whom a daughter was born to him named Marium Khanam, well known as Munnu jan Khanam it was round this only child that all the affections of the father centred. He died at the age of 78, while his daughter was only seven years old, bequeathing all his properties to her and appointing his sister Sonhaji Faizulla to be the guardian of his daughter and his property. Haji Faizulla was then at Surat and returned after five months and took charge of Munnu Jan Khannam and her properties. He managed the properties very ably and honestly. He then, married Zainab Khanam, who was then young, fearing that she might marry another person and thus create troubles for him and her daughter, the only fruit of his happy union was the famous Haji Mohammed Mohsin.

Haji Mohammed Mohsin was 8 years (and some says 14 years) younger than his step sister, and both of them was brought up together in the house hold of Haji Faizulla. From the earliest year the sister tenderly watched him, taught him Arabic and Persian. When he sufficiently advanced in his studies she kept him under the care of Persian tutor, Agha Shirazi, who was a man of considerable learning and experience, having travelled in various countries, after having left his original house in Shiraz, and continued his studies as his fellow pupil. It was the spirit of the tutor, who often related his experience and the stories of his own adventure that nurtured in pupil thus early the intense desire for travel which he gratified in after years. Finally to complete the education in Koran and the classes he went to Murshidabad, and became a scholar of one of the most famous institution of the times. Having finished the life of scholars and laden with the rich fruits of learning, he returned to his sister’s home at Hooghly and now bestowed all his care and affection to relieve his sister from the onerous duties and anxious life which her wealth and position had imposed on her. He gave a ready proof of his affection by informing his sister in time of the plot that was hatched up to poison her. This discovery created many enemies for him and finding his position risky, he left Hooghly when he was quite young, but not untill his sister was ready to marry and so would not be left without protection.

He now lost no time in setting out to see the world. His travel began at a time when the Mughals were tottering and India was at the beginning of a great transition. Visiting all the famous place of Northern India he travelled far beyond the limits of the Mughal Empire. He went to Arabia, performed Hajj, visited Medina and started for Najaf. During his journey to Najaf he fell into the hands of robber, who treated him mercilessly, robbing him of everything that was with him. He was then 32 years old. Poor and desolate, he wandered for seven years from place to place in Iraq, Arab, Mesopotamia, quenching his thirst of knowledge and travel. He then preceded to Persia, reached his original home, Isphan, where he was warmly and hospitably received. For search of knowledge he had the longing for the fountain of his paternal home and he went to visit the shrine and enjoyed the company of the learned men in Khorasan. He also visited Turkey and Egypt. He spent 27 years of life in travel, and the weary traveller now, of sixty years of age, naturally wished to return to the land of his birth and in company of his friend of Isphan he at last safely arrived in India. He visited all the famous places of the Muslim world and thus added to his large stock of knowledge, fresh wisdom, and widened vision which he had acquired from each new source. During his travel his fame had reached far and wide and when he reached India he found everywhere a great reception ready for him. He stayed for many months at Delhi, Lucknow, Banaras and Patna. Nawab Asifud Dowla expressed a great desire to have an interview with Haji Mohammed Mohsin, with an intention of persuading the great scholar to remain in his kingdom and to form an ornament of his court, but he thankfully refused the offer and after a short stay returned at last to Murshidabad, whence he had set out so many years before. Now he became to pass his days living sometimes at Dacca and sometimes at Murshidabad. This ascetic life of Haji combined with his immense learning and unspotted character gained for him the universal respect. He used to feed the poor, provide clothes to the naked, entertain guest for months together. Being not a rich man yet he used to help the poor by handing over to them a copy of Quran written in his own noted hand-writing for which any one could pay Rs. 1,000/-. It is said with authenticity that he made 72 copies of the holy Qumran and distributed them in like manner to deserving men. One book is still at Hooghly Mohsin College Library. He had the mastery over all the 7 kinds of penmanship. He was of versatile talents. He was a great theologian, an accomplished traditionalist and a first rated commentator on the Holy Quran. He was a good historian and a sound mathematician. He had learned English also in his old age, and could speak Urdu fluently. He knew the art of sewing and cooking and could use all weapon of attack with considerable skill. He could play music very well. He was a great swordsman and a expert pedestrian, a skilful mechanic and a powerful wrestler. But he never used the strength of his body or of his sword to defend the weak against the strong. He always used to walk on foot every morning for 3 or 4miles.His dress was very plain and his manners simple and attractive. Two or three ordinary turbans, a course garment and a sheet served his purpose for a long time. He like the acquaintance of the poor kept himself aloof from the society of wealth and well - to - do men. Nawab Nazim Mobarakud Dowla Subadar of Bengal used often to visit him, but the Haji never went to the Nawabs palace.

Great were the changes during the long absence of the Haji from Hooghly. His sister had married Mirza Salahuddin Mohammed Khan, of Isphan, who having own the favours of Mohabbat Jung, Nawab Nazim of Bengal, by concluding a treaty with the Marhatas favourable with the Nawab, was at that time the faujdar of Hooghly. The marriage proved a very happy one. Their life passed smoothly. They spent a good deal in charity and pious purpose and their by endeared themselves to the people in the neighbourhood. They spent a good deal in charity and pious purpose and thereby endeared themselves to the people in the neighbourhood.

In 1735, they extended the building of the Imambarah begun by Agha Motahar adding a portion which was termed "Tazia Khana" and close by, Mirza Salahuddin established at Hat which still bears it name. The present grant edifice of the Imambarah was built on the site of the building by the great Mutawalli Syed Karamt Ali of Jaunpur. Maulvi Syed Keramat Ali by his service in the Afghan War attracted the notice of Lord Auckland and was appointed Mutawalli of the Hooghly Imambara in 1836. He was a very able and learned man. He was a good mathematician and a scientist. Syed Keramat Ali tried to trisect an acute angle geometrically, and nearly succeeded in his attempt. He was most outstanding man and for his Civil Services Examination for which the Directors of the East India Company presented him with a valuable watch with the inscription "Awarded to Mir Keramat Ali". The most important work during his time was the construction of the handsome Imambarah Building with its clock tower and sundial chiefly according to his plan and under his superintendence. He died on the 10th September 1875. But the happiness of the married pair was transitory. Mirza Salahuddin died in the prime of his life. The loss of the useful and the able husband was a great blow to Mannu Jan Khanum. But wise and true as she was, she remained to the memory of her husband, managing her property with tact and ability. The papers showed that she recovered the property of Sobhna which had been to the Government after the death of her husband. Her bold denial to accept the hand of Khan Jaman Khan, of Hooghly, is lasting proof of her wisdom and fidelity. Like her father she regarded the wealth to be the property of the sinless Imams, and continued the observance of Moharrum and other religious ceremonious peculiar to the Shia sect in the same spirit and scale.

Old as she was now, the management of her vast estates seemed too heavy a burden on her. She naturally longed to have the assistance now of her step-brother, Haji Mohammed Mohsin, who was so dear to her and whom she knew to be the honest and competent. She entreated him to come to her relief from Murshidabad and although Haji Mohammed Mohsin was determined to pass his life as a scholar and ascetic there, he could not help acceding to the request of the constant companion of his childhood for whom he had special regard and attachment. Accordingly he returned to Hooghly accompanied by his two friends Rajab Ali Khan and Shakir Ali Khan, and was accorded a warm reception by his sister who made over to him all the papers and management of all her property, and herself adopted a schedule life. To the credit of Haji Mohammad Mohsin it might be said that in spite of perfect aloofness from worldly affairs, he managed the Zamindari with great ability, tact and judgement. This sister passed her days in prayer, tenderly carried for by her brother, and died at the age of 81, in 1803 A.D.

Haji Mohammed Mohsin inherited all the property of his sister which she had left by a will to him as the last and enduring proof of her affection. It was thus at the age of 73 years that Haji Mohammed Mohsin became the legal heir of this vast acquisition, which he put to God. But unlike ordinary mortals his enormous wealth brought no change in him. He remained what he was, an intensely pious man living the frugal life of the traveller and scholar. He did not marry despite the earnest solicitation of his sister. The loneliness gave him ample opportunities to cultivate those virtues and prepared his mind for receiving those impression which was reflected in the on the world in beautiful prismatic diffraction. His wealth only widened the sphere of his affection and charity. It gave him opportunity to serve the suffering humanity in more efficient and approaching manner. Not to say in helping those who came to him, he even wandered from door to door seeking out the needy gentleman, the starving widow and the distressed orphan. The love of man was the keynote of his life, and this be taught us not in theory but by percept and example. There are several interesting episode illustrating his magnanimity and large hearted charity.

Like his sister and his father he was now anxious to turn the course of his charity into a more useful channel by dedicating his property to the service of God, and Prophet and the sinless Imams to whom only he owed all his pity and large - heartedness. With objects in view and contemplating his death not far off, he on April 20th , 1806 A.D. signed a deed of trust, setting apart the whole of his income for the fathea of the Prophet and the Imams, for the expense of Moharrum and for all other days of feast and festivals which had been the established practice of this great family from the days of Agha Motahar. A copy of the deed both in English and Persian is inscribed on the walls of the Hooghly Imambarah, facing the Hooghly River, in which the donor has clearly defined his intention and purpose in creating this endowment. The deed after giving some account of the founder of the property which formed the subject of the endowment and also of the founders full wish and the desire to keep up and continue and usages and charitable expenses of the Fathea etc. (Marasim - wa - Akhrajat - i - Hussainiah) of the Hazrat (whom be blessing and reward) and of the sinless Imams (on all of whom be the blessing God) which have been the established practice of the family, went on to state that the entire income of the property after paying the Government revenues were to be divided into 9 equal shares. (A) 3 shares were to applied in the expenditure of Ashra of Moharram - al - Haram (ten days of sacred Moharrum) and all other days of feast and festivals, and in the repair of the Imambarah and the cemetery.

(B) 2 shares in equal portion to be allotted as remuneration of the two mutawallis appointed to supervise the religious and zamindari affairs of the endowments;

(c) 4 shares to be disbursed in the payment of the establishment, monthly stipends of the stipendiary’s, respectable men, peadasan and other persons.

This is the summary of the Haji Mohammed Mohsin’s purpose in giving the whole of his property for the sake of God, his religion and his salvation in conformity with the Imamiah faith in permanent appropriation. I will relate briefly in other place how the trust property of Haji Mohammad Mohsin is now managed and how it proceeds is at present appropriated.